Demetrius Wren is a filmmaker, musician, and storyteller based in Los Angeles. He has told stories in the form of award winning documentaries, feature narratives, and short films. In 2018, he partnered with IFTF to create 3 short films exploring how the changing nature of work could impact the health of workers, their families, and communities over the next decade.

In early July, IFTF Research Director Rachel Maguire, who led the work investigating the future of work and the potential impacts on health, and Demetrius met up (over Zoom) to talk about the intersection of storytelling and futures work. Below is an excerpt from their conversation (edited for length and clarity).

Rachel: So, let’s get to it. You have said that “filmmaking is the people’s art.” Why do you think that?

Demetrius: Every generation has an art form that seems more universal. Maybe back in the day it was music, at other times it was plays, and at other points it was art. Right now, it’s filmmaking, it’s storytelling in the visual. Filmmaking speaks to us in our current time and generation.

Rachel: You also maintain that filmmaking “can create social change, educate, validate, and uncover the highest truths.” Why is filmmaking such a potent medium?

Demetrius: As humans, when we see something, we feel like we were there. You think about George Floyd. Filming [his murder] was the catalyst because people could watch the video and see it. People have been writing articles and books about racial injustice for a long time, but it was that visceral of seeing it and feeling like you were actually witnessing something that causes that change. There is a certain level of truth, too. The ‘close up,’ even in narrative filmmaking, reveals truth.

Rachel: Good futures work should offer people complex, creative, and compelling depictions of plausible but also provocative views of the longer-term future. In that respect, it seems similar to storytelling. How would you compare and contrast futures work to storytelling?

Demetrius: In futures work, there is a tendency to want to push something to the furthest degree, and it’s no longer connected to humanity. It focuses too much on the drivers shaping the future, but the best stories are always about these human problems that we’ll always face because we’re human beings. Whether you are telling a story about living on Mars, or in the Middle Ages, or ten years into the future, you’re still going to wonder how you’re going to raise your children or if you did the right thing with your parents or if you’re going to fall in love, if you’re going to make friends. Blending storytelling and futures work is a way to blend analytical futures work with the universal human condition. It shows the choices people are forced to make and what choices are available to them.

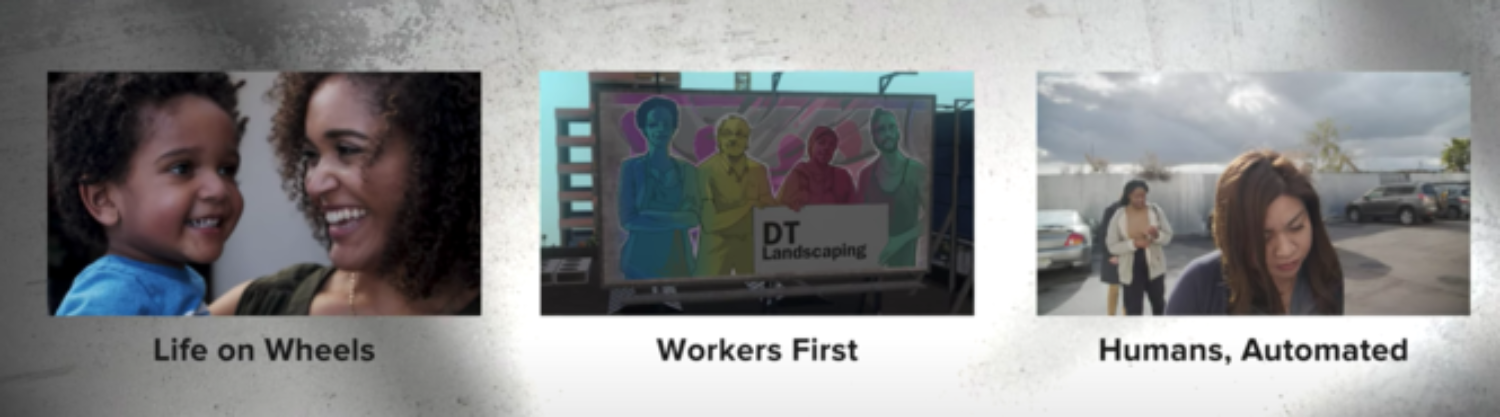

Rachel: The work we did together explored three possibilities for the future of work, and what that might mean for how we understand the health of workers, their families, and their communities. We wanted viewers to immerse themselves in these “stories from the future” but to do so with an eye to the present. We wanted these depictions of new and increasing health risks as a result of changing practices and ways of working to drive actions in the present. You make art that is, as you say, “full of immediacy.” How did you bring that same sense of urgency into stories that were set in 2030?

Demetrius: You have to craft a story that speaks to some of the things they are thinking about today and show how they could be particularly different in the future. Then, through the storytelling, you help people map back to a very real present problem that you’re trying to solve today. For example, in the short film “Life on Wheels,” the story was: I’m a person, looking to find a place to stay for me and my kid that can work with my lifestyle. That is a very human thing, but, in the story we created, she’s doing this very normal thing in a future filled with these new kinds of car parks.

Rachel: A tension we had to resolve while making these short films was how to show that these scenarios were based on extensive research. In storytelling, how do you balance the need to show the evidence without boring the audience?

Demetrius: If we stick with “Life on Wheels,” we didn’t lead with all the data and research that was justifying the future conditions that surrounded the mom who was looking for a place for her and her son. I didn’t want to give [the viewers] the data and research upfront because that just washes over the viewer as just a bunch of information. Instead, we showed them the end result which made them curious to understand how we got to that future.

Rachel: I learned a tremendous amount from your ability to both tell and show a story, which I hope to bring into all my futures work moving forward. Anything that you learned from futures work that you’ll bring to filmmaking?

Demetrius: The work of “world building” which is part of storytelling, particularly sci-fi, and the alternative futures methodology framework used in futures work bring a level of discipline to storytelling. If you are creating a transformational world, for example, you have to reflect this transformational future not just in the storytelling or the characters, but in the package design and the set design.

Rachel: What lessons can foresight practitioners take from filmmaking and apply to their foresight practice?

Demetrius: People like to be told a story. A story that has a beginning, middle, and end with peaks and valleys of excitement, concern, and understanding. Audiences prefer to have personal attachment to a possible future instead of a complex statistic on how that possible future came to be. Even the best journalism evokes a sense of immediacy and personality in its telling of facts. When revealing your research, always find an individual (whether it’s a person invented for the future scenario or one that is gathered from the on-the-ground research) that can help personify and ground the data in reality. It’s not simply a story of “how a particular industry can adjust for a given scenario” but “in this scenario, we find Jeremiah who is being affected in these important ways in their day-to-day life.” Give the reader or viewer cliffhangers, exciting incidents, suspense, and resolution that are grounded in the research.

Want to receive free tips, tools, and advice for your foresight practice from the world's leading futures organization? Subscribe to the IFTF Foresight Essentials newsletter to get monthly updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ready to become a professional futurist? Learn future-ready skills by enrolling in an IFTF Foresight Essentials training based on 50+ years of time-tested and proven foresight tools and methods today. Learn more ».