On a hot July day in Northern California, IFTF researchers Ben Hamamoto and Rachel Maguire, with almost 30 years of experience in futures work between them, sat down to reflect on health-focused forecasts they had developed over ten years ago, focusing particularly on those predictions that did not unfold as they had anticipated. What follows is an excerpt of their enlightening conversation, which, we hope, will enhance your own forecasting skills and broaden your perspective on the possibilities and limitations of futures thinking.

Rachel: Alright, Ben, let’s start with the facts. I started at IFTF in 2006. What about you?

Ben: 2011, five years after you. Do you remember one of your first forecasts?

Rachel: Of course! You never forget your first forecast. One of my first areas of research at IFTF was the future of new media and health.

Ben: New media?

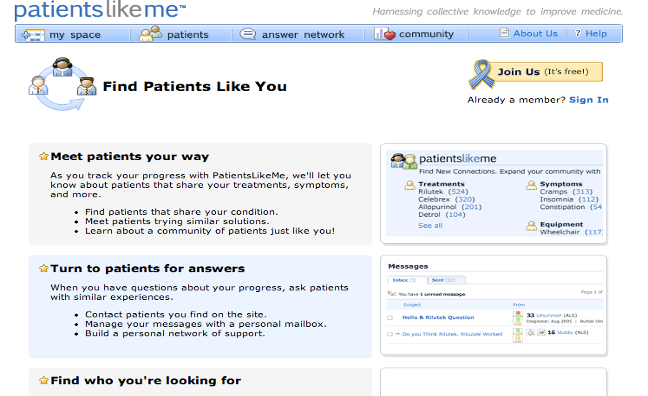

Rachel: It’s what we now refer to as social media. At the time, the idea of strangers talking to each other about shared health diagnoses or conditions was uprooting a number of assumptions around how patients (aka people) get informed about their own health and care.

Ben: Because people were relying on new sources?

Rachel: Yeah, in fact, I think we called them new information authorities. I remember we shared the example “brain fog” which is a common side effect of certain breast cancer drugs. Before these websites existed, people would share the symptoms of brain fog or “chemo brain” with their doctors and be largely ignored. Once those afflicted found each other on these so-called “health-related social networking sites,” they were able to demand illness recognition through collective action. Based on this, we forecasted that people would form biosocial groups online that would increase access to knowledge and contest claims of expertise.

Ben: What was the response from IFTF partners when this forecast was presented?

Rachel: There was a lot of concern about the veracity of the information, and the health risks associated with the spread of bad information across these online networks. And I remember someone from the pharmaceutical industry predicting that pharmaceutical companies would never be able to engage with these communities for liability reasons, especially if the discussions included conversations about off-label use of their products or interactions of their products with other over-the-counter drugs. But we forecasted that these new biosocial groups would be an effective way to campaign for better treatments, end stigma, gain access to services, and get involved in research participation.

Ben: And today we can see evidence of all those activities underway across social media.

Rachel: Exactly. There were signals of all of it back then, but nothing like what it looks like today in terms of the scale. What about you? What early forecasts come to your mind?

Ben: The forecast you mentioned actually makes me think about our early work at the intersection of health and narrative. We had a set of forecasts in 2012 and 2013 that were trying to highlight how important storytelling is to health behavior and health outcomes, and project where that could go in a decade. In our 2012 map, Information Ecosystems of Well-being, we had a forecast called “Quantified Storytelling,” that was about being able to measure the importance or impact of communication.

The keystone signal we used for it was the Special Care Clinic, run by Dr. Rushika Fernandopulle, that was able to drastically reduce costs and improve outcomes for its patient population, which was mostly low-income people struggling with multiple chronic health conditions. And the way they were able to do that was by employing health coaches who mostly didn’t have any prior medical training, but were great at customer service and, maybe more importantly, came from the same community as the people they were serving. Looking back at this forecast, I think the content was really useful for our partners.

Then in 2013, we created the “Reworking Health: New Authorities in a Well-being Economy” map. Our research led us to map potential authorities and trusted providers of health and well-being information and services. And we identified four big forecast categories: Computation, Ambience, Networks, and Narratives.

There was a forecast in Ambience called “The Care Effect” that was based on studies that found you can make the placebo effect more powerful by providing treatments in an atmosphere that communicates a high level of care to the person receiving the treatment, i.e. a clean, warm room with soothing music and pleasant scents; a care provider who listens and responds empathetically, etc. I recently listened to an interview with Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling, author of the book, If It Sounds Like a Quack…, about fringe medicine, and when asked about the appeal of these kinds of sham treatments, he said that the people he interviewed told him that one reason they found these medical grifters persuasive, was that they treated them with dignity, seemed happy they were there, or were eager to help, as opposed to providers they interacted within the conventional medical system who talked down to them and treated them like a burden.

Rachel: How was this forecast received?

Ben: At the time, a lot of entities that held authority in the health and well-being space could see that authority slipping away, and felt it was bad for both themselves and society. And on some level, they were maybe right. They were afraid of a future in which “being correct” didn’t hold as much importance as “having the right narrative or being part of the right network.” So, we took that into account and created forecasts that weren’t about what an awful thing that would be. I think what we were trying to communicate was that this *can* be a positive future *if* the entities with the “correct” information and approaches to health are also those that “have the right narrative” and are “part of the right network.” And that is part of the world we live in today. Watching Dr. Fernandopulle over the last decade has been interesting; he’s been able to expand and scale his model into a company called Iora Health, which was purchased last year by One Medical. At the same time, we’ve seen a lot of people use these “new sources of authority” as we called them in the map, for purposes that aren’t really improving well-being.

Rachel: It’s worth mentioning that evaluating past forecasts by how right they were or how well they predicted the future is not the central point of forecasting. That said, I think our forecasting on the directions that information and narrative were headed turned out to be fairly correct.

Ben: Agreed. What is an area that you’d say our forecasts from a decade ago do not seem to reflect the present?

Rachel: The future of self-care. We were really ambitious about how quickly the more robust understanding of what produces health and what keeps us healthy that was gaining steam in the early 2010 would convert into new self-care practices.

Ben: Making self-care a passive, almost, effortless activity, right?

Rachel: Exactly! It was a logical forecast: Once we have all this information about our health at our fingertips, we’ll be able to take action to preserve, protect, or fix our health. In 2012, we wrote, “By 2022, we’ll see innovators creating tools to harness the flow of data and make it actionable.”

Ben: Logic can be a dangerous element in forecasting…

Rachel: Or at least one worth examining. If the point was to get the future “right,” our forecasts on self-care would have needed to reflect the headwinds that would prevent how we take care of ourselves to change in any substantive way. We did seem to appreciate that it would take time. In fact, in 2012 we created artifacts from the future, but we extended our view to 2032 as opposed to 2022. One of the artifacts was a service that could serve up a tablet tailored to the client’s precise health needs. It also included food ordering and exercise regimes, all responsive to an individual’s present state.

Ben: I take your point that we anticipated a pace of change in automated and passive self-care practices that has not borne out over the last decade, but I would argue that we were also trying to provoke a new way of thinking about self-care. At the time, information was seen as the resource that people were lacking. If they just had more information “at their fingertips” whether through mobile phone apps or the web, they’d be able to make better decisions about their health and well-being. We were pushing back on that assumption — and our forecasts and artifacts were illuminating — that information was often not the missing resource in people’s lives. Many had the information about how to be healthy, but they didn’t have the time, or the money or the ability to act on that information.

Rachel: Right. And all of this personalized health information, first on the mobile phone and then through wearables, was just adding to the onslaught of information.

Ben: And putting more of the burden on people to act on this information, even when they didn’t have the means to.

Rachel: So there is value in forecasting what is possible as opposed to what is likely, especially in areas in which change tends to be slow.

Ben: Yeah, absolutely. I think maybe the common denominator in all these forecasts from that period, whether they were focused on narrative or automation, was that at their core, they were about how information is important, but insufficient on its own to affect change. What they were depicting was a future in which those in the health space took that to heart.

IFTF Foresight Essentials

Institute for the Future (IFTF) is the world’s leading futures organization. Its training program, IFTF Foresight Essentials, is a comprehensive portfolio of strategic foresight training tools based upon over 50 years of IFTF methodologies. IFTF Foresight Essentials cultivates a foresight mindset and skillset that enable individuals and organizations to foresee future forces, identify emerging imperatives, and develop world-ready strategies. To learn more about how IFTF Foresight Essentials is uniquely customizable for businesses, government agencies, and social impact organizations, visit iftf.org/foresightessentials or subscribe to the IFTF Foresight Essentials newsletter.

Read on the Foresight Matters Medium Channel here.